Why You (and Everyone Else) Makes Bad Decisions

To understand why humans make bad decisions at times, we have to understand the purpose of emotions. Imagine that you are in a jungle 25,000 years ago and you spot a tiger stalking you.

Do you want to start making a pros and cons list of what to do and weigh all of your options carefully? Of course not, you would be dead before you got to write down the second pro on your whiteboard. What you would want was an automatic decision-making system that could make a split-second decision to turn your tail and run before you had time to think. In comes emotions to the rescue, generating a strong feeling to act before the rational mind could process what was going on. Emotions kept our ancestors alive from immediate threats while their rational mind planned for the future. This duality of decision-making between non-conscious reactions and conscious thought leads us to the first reason you make bad decisions:

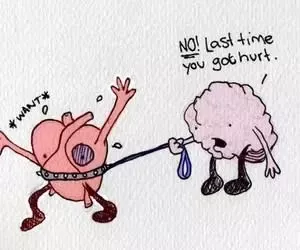

1. Humans are of two minds

Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel prize winner for his research about human judgment and decision-making, created a dual-system framework to explain why our decisions are often not rational. System 1 consists of thinking processes that are intuitive, automatic, experience-based, and relatively unconscious. System 2 is more reflective, controlled, deliberative, and analytical. In general, System 1 is something like a gut feeling from first impressions while System 2 is the rational babysitter that keeps a check on our behavior (often unsuccessfully). While emotions serve an important role in decision-making, we can be carried away by them if we let them.

2. Humans are limited beings

Whether we like it or not, humans are limited when it comes to decision-making. We often have limited knowledge, time, energy, and attention. After getting home exhausted from a 12-hour shift, the pizza rolls in the freezer start to look a lot more appealing even when you know rationally that your goal is to lose weight. There is also no information guide for if that particular person is the right person to marry or if that particular career will leave you fulfilled. There are also millions of things we could focus on at any moment, and often we just do not see that a better option exists or how to follow through on our intentions. So how do we handle these limitations?

3. Our minds use shortcuts

Because there is so much information out there and our brain takes a huge amount of energy to run, our brains need to be efficient. To do this, our mind uses mental shortcuts such as heuristics, biases, and habits to make decisions. These shortcuts help us tremendously to navigate our noisy world, but sometimes they can lead to us acting against our best intentions. Here are some common shortcuts that undermine most people daily:

- Present bias: We overvalue immediate rewards and undervalue long-term consequences. This was useful when food and shelter were uncertain for humans. It can promote procrastination because Netflix is much better than studying for your Calculus exam.

- Novelty bias: We see new things as better. This was useful to make humans search out rewards such as food for survival and new mates to pass on genes. It can promote endless social media scrolling as we are constantly rewarded with novel "information".

- Negativity bias: We are more prone to remember negative events than positive events. This was useful when doing something wrong could mean being exiled from your tribe (almost certain death). This can promote low self-worth as people more readily remember what they did poorly than what they have done well.

Learning these 3 biases alone gave me several "whoa" moments that explained a lot of why I hadn't followed through with my intentions in the past.

4. Our behavior is deeply affected by the context we are in

Our behavior is shaped in obvious ways by context such as Bird scooters lying everywhere urging us to ride them. Our behavior is shaped in many non-obvious ways as well. People we talk to, what we interact with, and our habits all plug into the equation for our decisions even if we can't directly see that. This context can make it easier to make poor decisions. For example, our social media environment is carefully curated to maximize your "time on site." Whether intentional or not, these companies exploit aspects of human psychology that keep many people scrolling when they would rather be doing something else.

Good news! You can do something about all of this

Luckily, there is the field of behavioral science that is helping us close the gap between our intentions and our actions. The basic message of behavioral science is that humans are hard-wired to make judgment errors and they need a nudge to make decisions that are in their own best interest. The understanding of where people go wrong can help people go right. Here is what you can do:

- Learn about a few biases that affect our decision-making. Here is a good start: 12 Common Biases That Affect How We Make Everyday Decisions. By learning about mental shortcuts like our natural tendency to be biased towards immediate rewards, we can catch bad decisions and explain why we might have had that urge (Hint: It's not something wrong with you).

- Frame problems in a better light. Because of the framing effect, how we frame the problems in our own life determines how we experience them. Do you see that obstacle in your life as a challenge or a threat? A great framework to view our decisions more clearly comes from Stoicism, which I wrote about here.

- Thoughtfully design a better context. We can set up our choices to make good decisions easier and bad decisions harder. Want to quit soda? Don't buy any at the store. Want to start running in the morning? Set out your workout clothes the night before. Want to use your phone less? Place it in another room while you are working. Small design choices can lead to a huge impact on behavior.

TL;DR

Humans make bad decisions because we have limited information and energy, our environment encourages bad decisions, and our brain takes mental shortcuts that often are not rational. We can improve our decisions by learning about mental shortcuts, framing our problems better, and designing our environment to encourage better decisions.